In case you haven't heard, 3D printing has entered the mainstream, and it will disrupt every industry's manufacturing processes slightly differently. Let's talk about why it will work in fashion.

3D printing is not entirely new to the fashion industry, as jewelry designers have for years outsourced quick modeling jobs to printing companies. But as 3D-printed pieces begin to pop up on the runway and in presentations outside of fashion week as the finished product, it's worth asking why the method stands a chance of proliferating among designers.

Catherine Wales, a designer trained in classic garment cutting at Yves Saint Laurent and Emanuel Ungaro, is currently exhibiting a collection of masks, corsets and helmets at the Arnhem Mode Biennale in the Netherlands. Designers Frances Bitonti and Michael Schmidt collaborated with Shapeways to produce a 3D-printed gown modeled by the burlesque icon Dita Von Teese at a presentation in February.

The results are beautiful. Comprising 3,000 articulated joints and dotted with 12,000 Swarovski crystals, Dita's gown fits her curves like a glittering Chinese finger trap. Wales's feathered shoulder piece fluffs and falls like the real thing.

This is art. It isn't wearable, but it suggests that 3D printing has the finesse necessary to break into an industry known for its attention to quality craft.

It is becoming more and more wearable.

Printers are getting closer to producing good fabric-like materials, using interlocking structures to create weaves and stitches. Duann Scott, Shapeways' "Designer Evangelist," said that once more fashion designers start using 3D printing, it will make a case for 3D manufacturers to develop more breathable, wearable materials. This is, of course, a chicken and egg situation, as designers aren't going to want to migrate to 3D printing until they know it's as good if not better than their current methods.

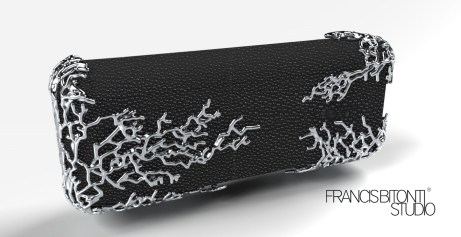

At the moment, 3D printing may be most compelling to designers when used in conjunction with organic materials. Bitonti told me that he's currently working on 3D-printed handbags finished with stingray leather, an idea that has a lot of potential. Designers and consumers have a strong historical and emotional affinity to non-synthetic materials like leather, silk and cotton, and they aren't going anywhere. It wouldn't be surprising to see designers incorporating complex printed elements with traditional materials in the near future.

It could save young designers.

If 3D printing disrupts mass fashion production, it will do so because it will have become cheaper and more efficient than current manufacturing methods. Ready-to-wear, however, with its smaller production runs, financial insecurity and impulse toward the artistic, is the ideal space for 3D printing to take root now.

The designer Kimberly Ovitz, who showed a small range of Shapeways-printed nylon jewelry with her ready-to-wear collection at New York Fashion Week in February, said that 3D printing revolutionized her production timetable. Consumers could buy the jewelry immediately after her show and receive the product in two weeks.

"I found that there are so many benefits for small designers. You don't have to deal with minimum or volume issues. You can design as many prototypes as you want as intricately as you want, and it doesn't affect anything the way it does with clothes."

For small, young brands, which have a failure rate not unlike tech startups, 3D printing offers the previously unheard-of option to manufacture exactly to order. In a world where botched manufacturing runs and over-estimated interest in an item leads to unusable and unsold stock, printing minimizes risk in a way that never existed before for fashion designers.

It can find a happy medium with handmade.

One of the obvious challenges facing mainstream adoption of 3D printing in the clothing industry is a longstanding appreciation for handcrafted pieces. Would a Birkin bag cost as much as it does if it were not stitched by human hands?

Scott argues that the traditional idea of handcraft is romanticized. Manipulating code to make a dress flow and fall over the human form is the new craft, he said.

But Scott is a Shapeways guy, and not all classically trained designers would agree. Anna Sheffield, a New York-based jewelry designer who experimented with printing finished products for an event sponsored by Shapeways at the Ace Hotel in February, told me that while she sees the advantages of using 3D printing to create a finished product, it's not right for her brand. She likes the slivers of imperfections that can result from casting.

"In some ways it can be used to enhance the design," she said. "But in other ways I think it leaves a generic motif on all of the goods, and to me it would be better to make the product and make a mold and cast it and finish or change it in some way. Hammer it. Something that gives it a more sensory feel. I'm a bit of a purist."

3D printing is, however, part of Sheffield's arsenal. While she often hand-makes wax models, Sheffield will go digital for repeating patterns, as on a ring of overlapping wheat sheaths. Scaling and altering designs on a CAD file reduces her workload by hours. For designers with an interest in preserving the uniqueness of handcrafted pieces, 3D printing could simply be a standard design tool to be used as needed.

If 3D printing is making moves on manufacturing in general, you can bet fashion won't be exempt, even if it is initially treated by the press as a futuristic conceit. It's dubious that the Fashion Institute of Technology and Parsons will start training their students as coders just yet, but printing could easily make inroads in accessories, shoes and non-fabric elements of clothing in the near future. It isn't hard to imagine that some of fashion's more avant-garde talents would be willing to experiment with printing in a more substantial way soon.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario